Victory over the Sun

in situ installation, reflective foil, artificial light projection

in situ installation, reflective foil, artificial light projection

ROMANTIC PARADOX

In haar artistieke praktijk gaat Kaat Van Doren een dialoog aan met de zon. De eerste ruimte in De Garage baadt in een oranjegele gloed, die misschien het licht van een romantische avondzon oproept. Anderzijds kleuren vervuilde luchten, bijvoorbeeld na een bosbrand, ook oranje. De zon liegt niet en toont gevolgen van de steeds urgentere klimaatproblematiek.

Aan het begin van de negentiende eeuw schilderden romantische kunstenaars zoals William Turner en Caspar David Friedrich spectaculaire luchten en zonsondergangen. Rond diezelfde tijd schreef Mary Shelley het eerste science fictionverhaal: Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus. Onderzoekers linken dit aan de uitbarsting van de Indonesische vulkaan Tambora in 1815. De wereldwijde weerkundige gevolgen, en de daarop volgende ‘zomer zonder zon’, bleken een onmiskenbare impact te hebben op de kunstenaars van die tijd.

De in situ installatie Waiting for Golden Hour is per defintie onaf: de kunstenaar markeert waar mogelijk het zonlicht binnenvalt. Doorheen de duur van de tentoonstelling verandert de stand van de zon; de installatie is dus nooit twee keer dezelfde. Als bezoeker is het wachten of de zon verschijnt en met welke impact. Maar “en attendant, il ne se passe rien:” wachten we als mens tevergeefs op het kortstondige romantische gouden uur, of op permanent vervuilde oranje luchten? De snelheid van de draaiing van de aarde staat in schril contrast met de traagheid waarmee de mens actie onderneemt om het klimaat te redden.

Het geduld dat de kunstenaar opbrengt om de zon te volgen, en de vertraging waartoe ze haar publiek in deze installatie uitnodigt, stroken niet met een kapitalistisch begrip van tijd. Het draait namelijk niet om rendabele productiviteit, maar enkel om het wachten, op iets waarvan we niet zeker weten dat het zal verschijnen. Het zonlicht is altijd voorwaardelijk en veranderlijk.

In dezelfde ruimte laat Van Doren een fragment van haar Post-Romantic Index: Between Bitumen and Sunlightdoorschemeren, een lijst begrippen die ze tijdens haar onderzoek tegenkwam. De zorgvuldige inventaris van wetenschappelijke of poëtische termen is een veruitwendiging van haar (en bij uitbreiding, het menselijke) verlangen om het natuurlijke fenomeen van de zon te (be)grijpen. Enerzijds probeert ze vat te krijgen op iets ongrijpbaars, anderzijds benadrukt de installatie de vrijheid en wilskracht van de zon. Zo verbeeldt ze de ambigue relatie van de mens met de natuur: aan de ene kant wil de westerse wetenschap die bestuderen en beheersen, aan de andere kant zal dit nooit volledig mogelijk zijn: de natuur laat zich niet temmen.

De paradox tussen een romantische schoonheid en de quasi-apocalyptische gloed van vervuiling, zit ook in het bitumen dat Van Doren gebruikt: een materiaal dat overblijft bij het destilleren van ruwe aardolie (die ontstaat uit fossiele resten die onder de aarde en de zee miljoenen jaren zonlicht opslaan). Het is een restproduct, maar ook een fascinerende en transformerende materie: bij warme temperaturen is het kleverig en vloeibaar, onder invloed van koude kan het hard en glanzend als glas worden. In de reeks Miroir Noir: Bitumina verheft de kunstenaar het harde, gebroken bitumen tot archeologische vondsten of edelstenen, waarvan de verleidende schoonheid nog versterkt is door de ondergaande zon die ze reflecteren.

Als de eerste ruimte in de tentoonstelling eerder immaterieel, efemeer of zelfs transcendent aandoet, dan is alles in de tweede ruimte net heel tastbaar. Het donkere bitumen past conceptueel en esthetisch in de industriële ruimte van De Garage. In 2017 bekleedde Van Doren een verlaten benzinestation, binnen én buiten, met bitumen. Door het diepe, kleverige zwart, lijkt het gebouw elk perspectief te verliezen en krijgt het een absorberende kracht, bijna als een zwart gat. Ook de zelfvormende plas bitumen, waarmee ze voor het eerst dit materiaal rechtstreeks in de tentoonstellingsruimte binnenbrengt, heeft dit effect.

Van Doren legt een historische link met de magie en de misleidende kracht van de zwarte spiegel waarin men in verschillende culturen en mythologieën toekomst en verleden las; van opborrelende aardolie in de Midden-Oosterse oudheid tot obsidiaan bij de Azteken. In de achttiende eeuw werd door Engelse amateurschilders weleens een zwart spiegeltje gebruikt in de zoektocht naar een ideaal landschap met sterke kleurcontrasten – à la Claude Lorrain, vandaar de gangbare term ‘Claude glass.’

Het gebruik van een ‘Claudespiegel’ is exemplarisch voor de romantische constructie van natuur. Onder andere in schilderkunst, maar ook in zorgvuldig ontworpen parken of tuinen, worden fictieve landschappen geïdealiseerd, terwijl de mens in werkelijkheid destructief handelt tegenover de natuur. Rond deze zeer dubbelzinnige verhouding, tussen schoonheid en (zelf)vernietiging, tussen het natuurlijke en het artificiële, tussen het existentiële en het ecologische, tussen wachten en arbeid, tussen bitumen en zonlicht, roept Van Dorens oeuvre vragen op.

Tamara Beheydt, curator

(ENG)

ROMANTIC PARADOX

In her artistic practice, Kaat Van Doren engages in a dialogue with the sun. The first space in De Garage is bathed in an orange-yellow glow, perhaps evoking the light of a romantic evening sun. On the other hand, polluted skies, for example after a forest fire, also turn orange. The sun does not lie, showing effects of increasingly pressing climate issues.

In the early nineteenth century, Romantic artists such as William Turner and Caspar David Friedrich painted spectacular skies and sunsets. Around the same time, Mary Shelley wrote the first science fiction story: Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus. Researchers link this to the 1815 eruption of the Indonesian volcano Tambora. The global meteorological consequences, and the subsequent 'summer without sun', proved to have an undeniable impact on the artists of the time.

The in situ installation Waiting for Golden Hour is by definition unfinished: the artist marks where possible sunlight enters. Throughout the duration of the exhibition, the position of the sun changes; so the installation is never the same twice.As a visitor, the wait is whether the sun appears and with what impact.But "en attendant, il ne se passe rien:" are we as humans waiting in vain for the brief romantic golden hour, or for permanently polluted orange skies?The speed of the earth's rotation contrasts sharply with the slowness with which humans take action to save the climate.

The artist's patience in following the sun, and the delay she invites her audience to in this installation, are not consistent with a capitalist understanding of time.For it is not about profitable productivity, but only about waiting, for something we are not sure will appear.Sunlight is always conditional and changeable.

In the same space, Van Doren hints at an excerpt from her Post-Romantic Index: Between Bitumen and Sunlight, a list of terms she came across during her research. The careful inventory of scientific or poetic terms is an externalisation of her (and by extension, human) desire to (grasp) the natural phenomenon of the sun.

On the one hand, she tries to get a grip on something intangible; on the other, the installation emphasises the freedom and willpower of the sun.In this way, she depicts man's ambiguous relationship with nature: on the one hand, Western science wants to study and control it; on the other, this will never be entirely possible: nature cannot be tamed.

The paradox between a romantic beauty and the quasi-apocalyptic glow of pollution, is also in the bitumen that Van Doren uses: a material left over from the distillation of crude oil (which is created from fossil remains that store sunlight under the earth and sea for millions of years). It is a residual product, but also a fascinating and transformative material: at warm temperatures it is sticky and liquid, under the influence of cold it can become hard and shiny like glass.In the series Miroir Noir: Bitumina, the artist elevates the hard, broken bitumen into archaeological finds or gems, whose seductive beauty is enhanced by the setting sun they reflect.

If the first space in the exhibition feels rather immaterial, ephemeral or even transcendent, everything in the second space is just very tangible. The dark bitumen fits conceptually and aesthetically into De Garage's industrial space.

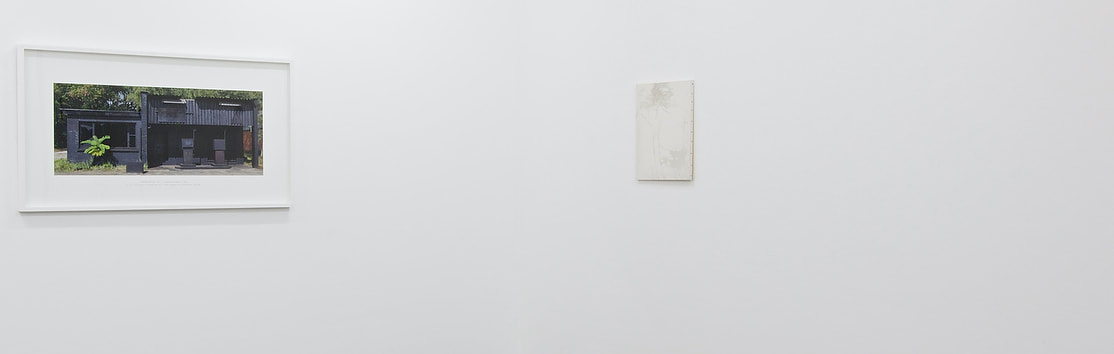

In 2017, Van Doren clad an abandoned petrol station, inside and out, with bitumen.

Because of the deep, sticky black, the building seems to lose all perspective and takes on an absorbing power, almost like a black hole. The self-forming puddle of bitumen, with which she brings this material directly into the exhibition space for the first time, also has this effect.

Van Doren makes a historical link to the magic and deceptive power of the black mirror in which people read future and past in different cultures and mythologies; from bubbling petroleum in Middle Eastern antiquity to obsidian among the Aztecs.In the 18th century, English amateur painters occasionally used a black mirror in the search for an ideal landscape with strong colour contrasts - à la Claude Lorrain, hence the common term 'Claude glass.'The use of a 'Claude mirror' exemplifies the romantic construction of nature. In painting, among other things, but also in carefully designed parks or gardens, fictional landscapes are idealised, while in reality humans act destructively towards nature. Around this very ambiguous relationship, between beauty and (self)destruction, between the natural and the artificial, between the existential and the ecological, between waiting and labour, between bitumen and sunlight, Van Dorens oeuvre raises questions.

Tamara Beheydt, curator

ROMANTIC PARADOX

In her artistic practice, Kaat Van Doren engages in a dialogue with the sun. The first space in De Garage is bathed in an orange-yellow glow, perhaps evoking the light of a romantic evening sun. On the other hand, polluted skies, for example after a forest fire, also turn orange. The sun does not lie, showing effects of increasingly pressing climate issues.

In the early nineteenth century, Romantic artists such as William Turner and Caspar David Friedrich painted spectacular skies and sunsets. Around the same time, Mary Shelley wrote the first science fiction story: Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus. Researchers link this to the 1815 eruption of the Indonesian volcano Tambora. The global meteorological consequences, and the subsequent 'summer without sun', proved to have an undeniable impact on the artists of the time.

The in situ installation Waiting for Golden Hour is by definition unfinished: the artist marks where possible sunlight enters. Throughout the duration of the exhibition, the position of the sun changes; so the installation is never the same twice.As a visitor, the wait is whether the sun appears and with what impact.But "en attendant, il ne se passe rien:" are we as humans waiting in vain for the brief romantic golden hour, or for permanently polluted orange skies?The speed of the earth's rotation contrasts sharply with the slowness with which humans take action to save the climate.

The artist's patience in following the sun, and the delay she invites her audience to in this installation, are not consistent with a capitalist understanding of time.For it is not about profitable productivity, but only about waiting, for something we are not sure will appear.Sunlight is always conditional and changeable.

In the same space, Van Doren hints at an excerpt from her Post-Romantic Index: Between Bitumen and Sunlight, a list of terms she came across during her research. The careful inventory of scientific or poetic terms is an externalisation of her (and by extension, human) desire to (grasp) the natural phenomenon of the sun.

On the one hand, she tries to get a grip on something intangible; on the other, the installation emphasises the freedom and willpower of the sun.In this way, she depicts man's ambiguous relationship with nature: on the one hand, Western science wants to study and control it; on the other, this will never be entirely possible: nature cannot be tamed.

The paradox between a romantic beauty and the quasi-apocalyptic glow of pollution, is also in the bitumen that Van Doren uses: a material left over from the distillation of crude oil (which is created from fossil remains that store sunlight under the earth and sea for millions of years). It is a residual product, but also a fascinating and transformative material: at warm temperatures it is sticky and liquid, under the influence of cold it can become hard and shiny like glass.In the series Miroir Noir: Bitumina, the artist elevates the hard, broken bitumen into archaeological finds or gems, whose seductive beauty is enhanced by the setting sun they reflect.

If the first space in the exhibition feels rather immaterial, ephemeral or even transcendent, everything in the second space is just very tangible. The dark bitumen fits conceptually and aesthetically into De Garage's industrial space.

In 2017, Van Doren clad an abandoned petrol station, inside and out, with bitumen.

Because of the deep, sticky black, the building seems to lose all perspective and takes on an absorbing power, almost like a black hole. The self-forming puddle of bitumen, with which she brings this material directly into the exhibition space for the first time, also has this effect.

Van Doren makes a historical link to the magic and deceptive power of the black mirror in which people read future and past in different cultures and mythologies; from bubbling petroleum in Middle Eastern antiquity to obsidian among the Aztecs.In the 18th century, English amateur painters occasionally used a black mirror in the search for an ideal landscape with strong colour contrasts - à la Claude Lorrain, hence the common term 'Claude glass.'The use of a 'Claude mirror' exemplifies the romantic construction of nature. In painting, among other things, but also in carefully designed parks or gardens, fictional landscapes are idealised, while in reality humans act destructively towards nature. Around this very ambiguous relationship, between beauty and (self)destruction, between the natural and the artificial, between the existential and the ecological, between waiting and labour, between bitumen and sunlight, Van Dorens oeuvre raises questions.

Tamara Beheydt, curator